Streamer University might as well have been called “How to Become Kai Cenat.”

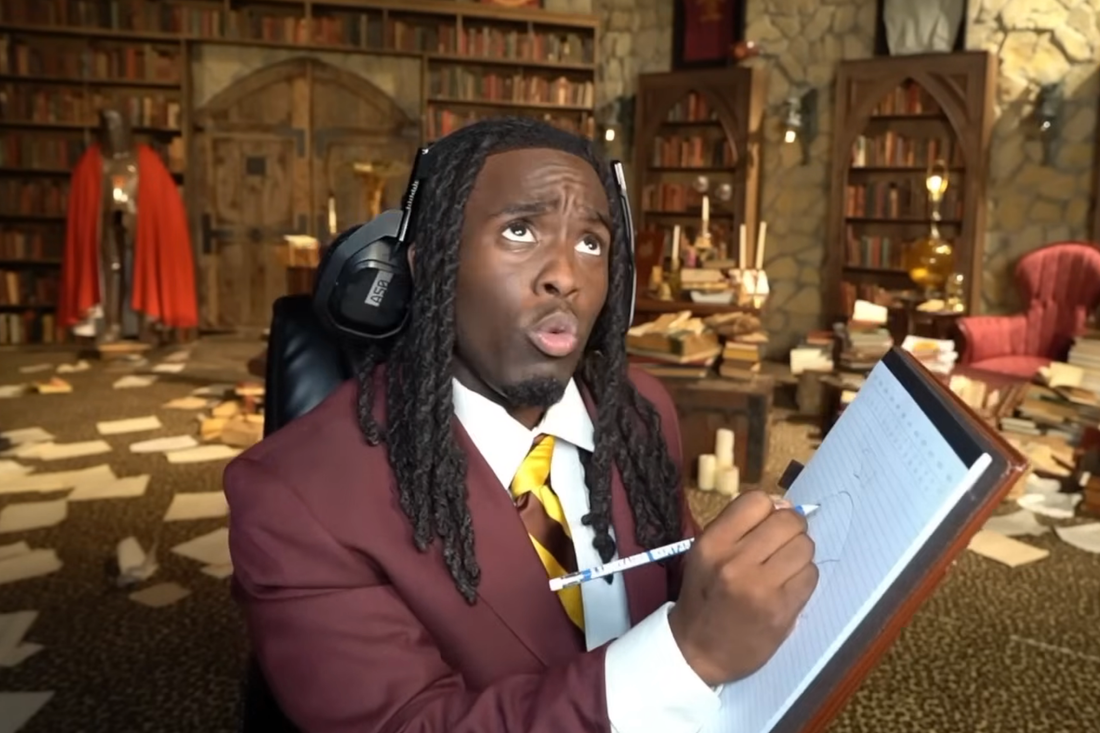

Photo: Kai Cenat Live via YouTube

During Winston Groves’s time at Streamer University, he endured all the worst parts of college in a single weekend. There was hazing — kids would come up to him and call him a bitch or tell him his hairline was “cooked.” Another left a hot dog in a condom on his doorknob. There was bad cafeteria food (“the eggs tasted like something off of Minecraft”) and nights where no one got more than four hours of sleep and most didn’t sleep at all. Most of all, there were smells. On the sixth floor where he stayed, which some referred to as “the demon floor,” people loaded waste bins with energy drinks, Cheetos, chips, baby powder, baby oil, confetti, and shaving cream and dumped them on unsuspecting passersby in what was called a “Glock Dookie Trash Can Splash.” “The whole floor smelled like wild fumes, mysterious funk,” he says. After being on the receiving end of one particularly nasty Glock Dookie, he described the stench as “so horrendous it didn’t even make no sense. And then I had a class at ten in the morning.”

It was also, for Groves and streamers like him, a dream come true. Groves, better known as his handle Big Winnn, was one of 120 students accepted into Streamer University, a weekend-long, all-expenses paid program where both established and nascent livestreamers could congregate, collaborate, and learn from each other while sharing the experience with their followers in real time. Picking up the tab was 23-year-old Kai Cenat, the event’s organizer and probably the most famous livestreamer in the world, whose hero status among young people rivals that of LeBron James or Drake. When he’d first made an offhand comment about his plans to launch a “streaming university” during a livestream in February, it wasn’t entirely clear whether the idea was purely theoretical. But when he released a Harry Potter–themed trailer for the program on May 6 announcing that enrollment was open for “a school where chaos is encouraged and content is king,” the website crashed within minutes after receiving more than a million applications, which involved filling out a Google form and submitting a 45-second video clip. The 120 acceptees, mostly in their late teens or early 20s, were announced 11 days later in a three-and-a-half-hour livestream, and less than a week after that, flown out to the University of Akron.

“To be honest with you, I thought it was a joke,” says University of Akron president R.J. Nemer. He’d received an Instagram DM that spring from Michael Matthews, a producer for Cenat who happened to be an alumnus, asking if the school would consider hosting a university for livestreamers. Once Nemer realized the offer was legit, he called his staff together and, despite some skepticism among the faculty, convinced them that this was an opportunity they couldn’t pass up. He knew, thanks to his background in sports and entertainment, that “this guy can grab attention and that was exciting for us, because it was exactly the demographic that we want.” Plans had to be sketched out in under a month, and the final rental contracts weren’t signed until just two weeks before May 22, when the streamers moved into Spanton Hall, a ten-story dorm in the University’s North Quad, all in total secrecy to prevent fans from surrounding the school. “I thought this was going to go one of two ways. It’s probably not going to be — as my kids would call it — mid, so it’s either going to be great or it’s going to be a disaster.”

The four-day event was designed as a boot camp for content creators who hoped to someday reign over their own empire of influence, having grown up watching how the hyperactive, over-the-top antics of YouTubers and Twitch streamers turned them into multimillionaire moguls. Classes, which ranged from “Monetization for Dummies” to “Internet Beef 101,” were taught by hugely popular creators in Cenat’s orbit like YouTuber Duke Dennis and Agent00. Twitch’s dedicated Streamer University page compiled the dozens of students and professors’ livestreams, where viewers could follow along either for pure entertainment or perhaps in the hopes that they too could learn the secrets of internet fame from their idols.

At a program whose tagline explicitly encourages chaos, it wasn’t a complete shock that things didn’t go exactly as planned. Logistical issues, like spotty Wi-Fi, especially on the first day, and chronic lateness plagued the weekend. Orientation began three hours late, and a planned dodgeball game and a pep rally involved hours of sitting around waiting for the events to begin. Students (and sometimes professors) would show up long after classes began after having barely slept the night before. “Most of us were going to bed at 3, 4, or 5 a.m. and waking up at 8. Some people were streaming through the night and streaming them[selves] sleeping,” says Allison Kroes, a 22-year-old gaming streamer from Michigan. Others, like 23-year-old Miami-based betrothed couple Alex Batista and Jessica Fuentes, said they slept only about an hour every night, and sometimes just 30 minutes.

On the sixth and seventh floors of Spanton Hall, where many of the younger and most rambunctious streamers lived, students doused the hallways, elevators, and dorm rooms with a spray designed to smell like farts. (“Oh, that’s what that was!” president Nemer replies when asked about what the cleanup process was like.) Hot dogs ended up all over the hallway floors. “They had this prank where they made fake poop with fart spray and it had literally stank up our room to the point where my roommate’s eyes were tearing up,” says Kieya Jennings, a 22-year-old from Indiana who goes by Barbieskie online. “[She] was literally scared to even walk out to the room, afraid she was gonna get pranked.” “There was water everywhere, baby oil, baby powder, noodles,” says Mari Franklin, a 24-year-old student from Texas who at one point fell and broke her toenail off. “The hallways were soaking wet, and people were slipping and falling,” adds Kroes. “It was like a war zone.” Groves literally describes the water-gun fights as “the war.”

Then there was the drama: One female student had to apologize to another after bullying her in her own comments section and making her cry. A physical fight between the teenage streamers Rakai and Dabo broke out over a ski mask. One night, after the YouTuber and rapper DDG, who has been accused in a restraining order filed by his ex Halle Bailey of physical and emotional abuse, bussed the students off campus to a nearby club, a random kid snuck into the dorms and roamed the hallways for four hours. Students would regularly yell out in class; one got kicked out for calling a professor “doo-doo garbage.” A girl was sent to the hospital after getting hit in the eye with an Orbee. There was, as tends to be the case with any event of this size, a COVID outbreak.

But all of it — the fights, the mess, the drama, even the water guns, which were handed out to students upon arrival — was intentional, if not always literally (no one would ever plan a COVID surge or a break-in) at least in spirit. Chaos is the fundamental ethos of livestreaming: In order to maintain viewers’ interest for hours at a time, particularly when those viewers are, for the most part, very young, have limited attention spans, and infinite other videos they could be watching, successful streamers must be loud, they must be large; they must manifest their emotions in a way that plays on-camera.

The goal of being a good streamer is to make your channel the one people want to watch out of the millions of others competing with you. “Beef” between stars is less UFC and more WWE: mostly acted moments of contention that can be clipped into viral videos — a practice called “clip farming” that all the most successful streamers do, hiring editors to cut for them and post to their socials. “Ninety percent of everyone was putting on a fake character,” explains Franklin, one of the students. “You have to have some kind of persona that causes a conversation. It has to be something that causes people to comment, because at the end of the day, if you have no engagement on your posts, you will not make it anywhere.” Often, creators will give each other a heads-up on what they’re about to do before they start filming.

Just as the “fighting” at Streamer University was mostly a joke, so too was the punishment. When DDG threw a gang sign while streaming, Cenat “caught” him and acted appalled, and when DDG had people in his room during one of the nightly lockdowns that took place when the hallway fighting got too rowdy, Cenat cut his stream to black and pretended to repeatedly smack him. Rakai, the 16-year-old enfant terrible of Streamer University who landed “Worst Behavior” at the final day’s awards ceremony, was threatened with expulsion multiple times, as were many others who were reprimanded by professors or called into Cenat’s “headmaster’s” office. “It got to a point where everybody started pushing the limits even more, just because they knew Kai wasn’t actually going to expel them,” says Batista.

A divide emerged, however, between the more established streamers who understood that they could get away with pretty much anything, and that in fact the entire point of Streamer University was that they could not only behave “badly” but get caught doing so, and the smaller creators who were terrified of losing their spot. “A lot of us felt like we missed opportunities in fear of getting expelled,” says Jennings. Smaller streamers, or those with fewer than around 50,000 or 100,000 followers, were also criticized by some of the professors and commenters online for “wasting” their time at Streamer U by not posting, clip farming, or putting themselves out there enough. Meanwhile, many spoke of intense social anxiety (Franklin, for instance, was so nervous on the first night she threw up) and a fear of getting “ego’d,” that is, rebuffed by someone more famous than you. On campus, with more than 120 cameras streaming at basically all times, the only moments where students were sure they wouldn’t be filmed was in the bathrooms. “If you ask anybody, they all cried. I think every single person in the school cried because it was so overwhelming,” says Jennings. (While many seemed to be happy tears, there was so much crying that people made compilation videos on TikTok.)

To be fair, it’s difficult even for hugely popular creators to know where the line is between reality and doing it for Twitch. In one moment, professor Agent00 arrives in his room to see several students pouring flour, silly string, and glitter all over his room and pins one of the offenders down, yelling at them all to “get the fuck out,” and that “it’s a difference between content! Learn the fucking difference!”

Though “learning” was the ostensible goal of Streamer University, Cenat, whose team did not reply to a request for comment, likely knows better than anyone that rizz can’t be taught in a classroom. Lessons, like physical education with YouTuber Duke Dennis to Love & Relationships with Instagram model and entrepreneur India Love, got somewhat mixed reviews, with many praising the tangible advice given in Agent00’s class on creator monetization and others criticizing a sex-education class, ironically, for being “too much like school.” DDG taught Internet Beef 101, in which his advice for winning an online rivalry included “diss they homies,” “roast they financés, even if you also broke,” and calling them a “bitch-ass n- – -a” or gay. (He later won MVP and the award for Best Professor.)

The unspoken impetus for organizing an event like this entirely on his own dime is, in part, to help Cenat cement himself as the reigning king of the streaming world, while at the same time acting as a talent incubator for promising up-and-comers. Streamer University might as well have been called “How to Become Kai Cenat.” Students spoke of him in an almost hagiographical manner, even if they couldn’t quite point to what makes him so compelling. Batista and Fuentes “almost blacked out” when they met him; as Groves says, “He got the Midas touch.” His fans, many of whom are kids and teenagers, say they love him for his inexhaustible energy. “A lot of random things happen out of nowhere,” a 16-year-old fan named Cece told me over Reddit about why she loves watching his streams. Za’taveon, a 14-year-old on Discord said, “He just has aura.” He hopes to become a streamer one day like Cenat, too.

For those in the industry, that ineffability is both difficult to replicate and needed more than ever. “There’s this frenetic energy, a hyperactivity that’s especially appealing to young men,” explains Grace Murray Vazquez, the executive VP of strategy at Fohr, an influencer marketing agency. “A lot of [them] are needing and craving excitement, and there’s a very human, real thing about wanting to experience that with a sense of togetherness.”

Jonathan Chanti, president of Viral Nation Talent, attributes some of Cenat’s success to timing: He’d already built a following on YouTube beginning in 2019 when he transitioned into streaming around 2021, a time when the medium was exploding. His streams were the perfect place for celebrities to promote their music at a time when the New Media Circuit was beginning to crystallize, bringing on everyone from Nicki Minaj to Ice Spice, Drake, and Snoop Dogg. He gamed, he chatted, he reacted to internet ephemera in a way that was contagious, popularizing slang terms like “chat” and “rizz” and amassing a fan base that lived entirely online. That was, until a 2023 giveaway in Union Square turned into a riot and revealed to the world just how big he — and the streaming industry — had become. “He kind of redefined the streaming landscape,” says Chanti, explaining that while Twitch was originally a platform most associated with gaming content, Cenat “gave complete access to everything [he was] thinking, speaking, talking about,” while simultaneously inviting his commenters — the “chat” — to interact with him in real time. It’s made him both wildly popular with fans, yes, but also with the major companies sponsoring him like McDonald’s and Nike that view him as a (mostly) wholesome and brand-safe ambassador. Cenat has hinted that he turned down offers from major platforms like Amazon Prime, Netflix, and Tubi to turn Streamer University into a “polished show,” but ultimately, his team estimated that over the course of the weekend, viewers consumed 23 million hours of footage from campus.

For the students at Streamer University, Cenat is living proof of what could happen to a regular kid from the Bronx and who at one point lived in a homeless shelter if they work very, very hard and get very, very lucky. It’s no wonder they were so emotional all weekend — Tylil James, who was awarded valedictorian and, perhaps more impressively, received a congratulatory call from Drake during a stream in which he accidentally leaked Drake’s number, recalls being “overwhelmed with love” and crying on the phone to his mom. “I knew I had to bring my A game, but I wanted to bring my A-plus game.” Batista and Fuentes say they plan to invite the whole dorm to their upcoming wedding. Every streamer I spoke to said the experience was, despite the Glock Dookies and the more disgusting elements of streamer dorm life, amazing, though they advised Cenat, should he renege on his vow to never hold another Streamer University again, to maybe keep men and women on separate floors, hire a therapist on campus, and “have fucking better food.” “You got this opportunity to change your family’s life,” says Groves. “You better give it all you got.”